“The walls around me and their guards in watches / cannot halt the full moon’s coming to my heart”

–Hermes, “The Djinn Falls in Love,”

translated from the Arabic by Robin Moger.

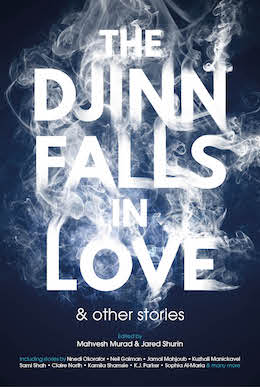

I rarely read anthologies. I’m picky about my short fiction, and I find that many anthologies will have, at best, two or three stories that speak to me. So when I say that The Djinn Falls in Love is a really good anthology, I mean it really works for me.

Mahvesh Murad may be best known around here for her “Midnight in Karachi” podcast, while Jared Shurin is one of the minds behind Pornokitsch. This anthology, they explain in their introduction, was a labour of love for them—one intended to showcase global storytelling, and also to showcase the djinn themselves. Their love for this work shines through in the care with which they’ve selected and arranged the stories. This anthology has a distinct shape and flavour, curling inwards from Kamila Shamsie’s lightly mythical story of fraternal longing and connection in “The Congregation” towards Amal El-Mohtar’s “A Tale of Ash in Seven Birds,” a metaphor wrapped in a story told with the rhythm of poetry, a story of immigration and transformation, and back out again towards Usman T. Malik’s quietly, thoroughly horrifying “Emperors of Jinn” and Nnedi Okorafor’s sly, sidelong “History,” part comedy and part commentary on exploitation.

Any anthology is going to have its standouts. And its duds. For me, there are only two stories in The Djinn Falls in Love that fall flat, Kirsty Logan’s “The Spite House,” which doesn’t distinguish itself very well in terms of a thematic argument —I also found its worldbuilding peculiarly confusing, and its conclusion unsatisfying—and James Smythe’s excessively oblique “The Sand in the Glass is Right,” which involves wishes and knowledge and multiple outcomes of the same life. (I found Sophia Al-Maria’s “The Righteous Guide of Arabsat” horrifying, but it was clearly intended to be so.)

But there are numerous outstanding stories here. Kamila Shamsie’s “The Congregation” opens the collection on a strong and striking note. J.Y. Yang’s “Glass Lights” is a bittersweet story of wishes and loneliness, and a woman who can make others’ wishes come true, but not her own. (It’s gorgeously written.) Saad Z. Hossein’s “Bring Your Own Spoon” is an affecting, uplifting story of friendship, fellowship, and food in a dystopian future. Sami Shah’s “Reap” is a creepy piece of effective horror told from the point of view of US drone operators. E.J. Swift’s “The Jinn Hunter’s Apprentice” sets a story of djinn and humans, possession and death, space exploration and science, on a Martian spaceport—and does it really, chillingly well. Maria Dahvana Headley’s “Black Powder” is an intoxicating story of wishes, consequences, love and alienation, beautifully written with utterly amazing prose. And Nnedi Okorafor’s “History” blends her trademark mixture of science and folklore with a helping of humour.

I think my two favourite stories from this collection are those by Helene Wecker and Claire North, though. Which says something about my prejudices and preferences, I suspect, as they’re the two stories that come closest to the rhythms and concerns of One Thousand and One Nights—and I’ve always had a weakness for medieval Arabic literature.

Claire North’s “Hurrem and the Djinn” is a story set in the court of Suleiman the Magnificent. A young man, who specialises in the study of djinn and such things, is approached to prove that Hurrem, the sultan’s favourite, is a witch. Told in the voice of a first person observer (one who doesn’t want to gossip), it’s a gorgeous story about men’s suspicion of women’s power—and of women’s power itself.

Helene Wecker’s “Majnun” is another gorgeous story—I’m using that word a lot about the stories in this anthology—where a djinn, former lover of the queen of the djinn, has become a devout Muslim and an exorcist. A confrontation with his old lover, who’s possessed a young boy, plays out in discussions of morality and philosophy and choices. It’s quiet and contemplative and all-around brilliant.

I really enjoyed this anthology. It is—here’s that word again—gorgeous. Its individual stories are mostly really good, and it has a strong sense of itself as a whole. This thematic coherence adds an extra element to the anthology as a whole: not just the individual stories, but their arrangement and relation to each other, have something to say.

I recommend it.

The Djinn Falls in Love and Other Stories is available now from Solaris.

Liz Bourke is a cranky queer person who reads books. She holds a Ph.D in Classics from Trinity College, Dublin. Find her at her blog. Or her Twitter. She supports the work of the Irish Refugee Council and the Abortion Rights Campaign.